It started with neck and foot pain.

Barbara Meyer-Mitchell of Norwalk didn’t think much of it, and she did not connect it to symptoms that followed.

“It was a cascade of: every six months to a year, I had a weird new thing,” she said. “I went to a specialist for each problem, and they weren’t linking them together.”

Her primary care doctor in Westport tested her seven times for Lyme disease, but each test returned negative. It wasn’t until nearly a decade after her first symptoms appeared that she tried a new method being developed to detect Lyme.

Today’s most common Lyme test looks not for the disease-causing organism itself but for the specific antibodies people’s immune systems manufacture in response. Those antibodies were not in Meyer-Mitchell’s bloodstream, perhaps because she had had the disease for so long. But the long squiggly spirochetes causing it were.

Meyer-Mitchell still remembers the swell of emotion she felt upon learning the diagnosis — finally, there was an explanation for the host of symptoms her team of specialists had not been able to solve.

The Advanced Laboratory Services Inc. lab in Pennsylvania, where the test was conducted, has had difficulty satisfying the scientific community that its test is reliable, but researchers agree on the importance of a test that can detect the disease itself. That’s why, in a Danbury laboratory, a team of Western Connecticut Health Network researchers are pursuing a method of identifying the disease by scanning for its genes.

In addition to being to diagnose people with Lyme whose bodies have not created antibodies, such a test allows people to diagnose the disease earlier (it generally takes two to three months before tests can detect antibodies) and to tell whether the disease has been successfully treated (antibodies can linger in the blood even after the organisms causing them have disappeared, creating potential for false positives).

In the microscope room, Lead Research Associate Srirupa Das watched a video the of the bacteria wiggling across a Petri dish. She said that with the antibody test, “You miss a lot of positive cases. And once it detects it, it is already late, you are already infected with Lyme disease for two or three months … By that time, the disease has already spread.”

Das said that being able to diagnose and start treatment early increased a patient’s chances of being cured. “That is why our research is so important.”

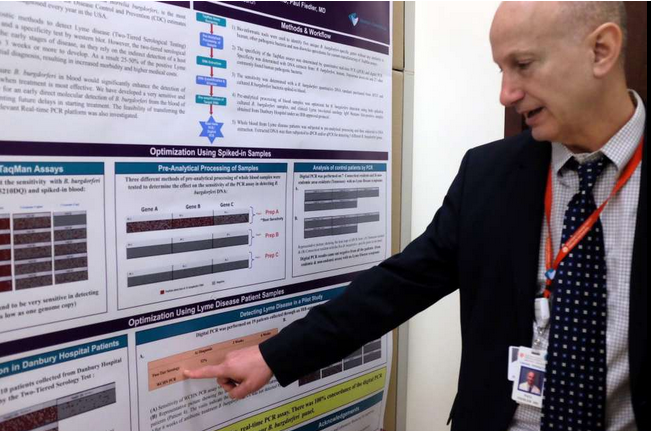

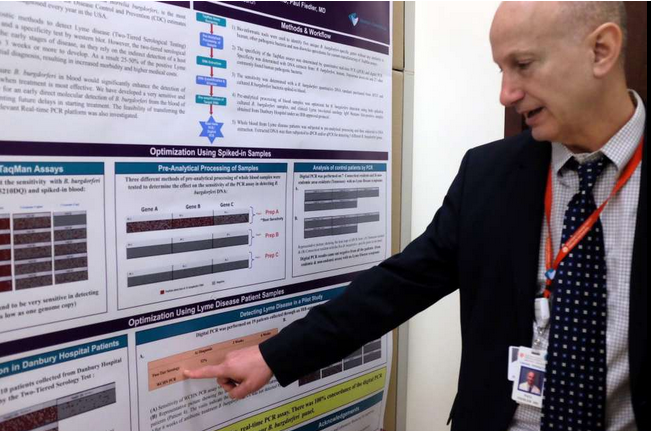

Paul Fiedler, a doctor researching Lyme disease at the Western Connecticut Health Network, pointed to a poster showing their team’s results.

“This is when we got really excited,” he said, indicating a chart comparing results from a traditional test to the results of the WCHN’s test as performed on 19 patients.

For the regular Lyme test, 32 percent of patients tested positive at the time of diagnosis, with that number increasing as patients returned to get retested two and six weeks later. In contrast, 63 percent of the patients tested by WCHN tested positive at diagnosis, and that number decreased over subsequent weeks as patients were treated.

However, even after three weeks of antibiotics, 44 percent of the WCHN patients still tested positive. “They’re supposed to be cured, right,” Fiedler said. “That’s what we want to follow.”

There is controversy over what causes Lyme disease symptoms to persist after treatment, Fiedler explained — some believe that it’s a prolonged infection (chronic Lyme disease), while others believes it’s a prolonged immune response causing problems.

Since an antibody-based test could not tell the difference between the two, WCHN’s gene-based test has the potential to finally answer the question. WCHN also home to the Lyme Disease Biobank, which has been collecting biological samples from people with Lyme disease since 2010. Fiedler said that another researcher had created a test for a number of tick-borne illnesses from a drop of blood, which could be used to look for patterns of how Lyme disease interacts with other infections.

The WCHN’s research, as Director of Public Relations Andrea Rynn, pointed out, is funded through philanthropy, and so the team recently launched a fundraising campaign, Taking Aim at Lyme (takingaimatlyme.org). Fiedler hopes the campaign will raise both funds and awareness.

Lyme season is gearing up, as young ticks — the smallest and most difficult to notice — are looking for hosts and people are spending more time outdoors.

At Wah Wah Taysee Scout Camp in North Haven, nestled near the foot of Sleeping Giant State Park, Ranger Ross Lanius came home Monday evening after clearing tree damage caused by the recent storm.

He pulled off four ticks.

“You just got to be careful and check yourself every night,” he said.

Experts say a tick’s bite needs to last over a day before the infection sets in. But spotting ticks can be harder than it seems.

The other night, Lanius thought he had gotten them all and readied to relax.

“And Lordy be, I sit down and there’s one on my other wrist,” he recalled.

Kirby Stafford, chief scientist and state etymologist at the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station in New Haven, tests for ticks in the environment by dragging a square yard of polar fleece along vegetation (he dresses in insecticide-treated clothes for protection) in addition to asking the public to send in ticks they find.

“Usually we get about 3,000 ticks submitted by the public, the majority from Fairfield and New Haven counties,” Stafford said. A year ago, following a very mild winter, he had roughly 5,000 ticks.

As for whether this year will be a bad one, he says it’s too early to tell. While this winter was also mild, it was long, and he says tick submissions in early 2018 weren’t as high as in 2017. What he can say is that he had seen an increase in Fairfield County’s submission of Lone Star ticks.

“So it’s not just the deer ticks or dog ticks that people have to look out for,” he cautioned.

If you find a tick, you can submit it to your local health department for testing. Theresa Argondezzi, a health educator at the Norwalk Health Department, explained that anyone can come in with a tick during normal health department hours. There, a scientist will identify the tick and send deer ticks to Stafford’s office in New Haven.

Argondezzi said her department send ticks off to the state for free for Norwalk residents (for non-Norwalk residents, it’s $15). She cautioned the tick should not be smooshed, taped or covered in any type of substance — instead, they should be sealed in a contained or plastic bag, then packaged in a padded envelope.

The WHCN Lyme Disease Biobank accepts samples from anyone who has ever been diagnosed with Lyme disease, regardless of location — those interested in participating should email [email protected].

“When you think about this, this is still a relatively new disease,” said Rynn of WHCN. Lyme was discovered in Lyme, Connecticut, in the 1970s.

“We’re working on that,” Das said.

[email protected]; @raschuetz